KWIF is Kent's Week in Film where each week Kent has a spotlight movie in which he writes a longer, thinkier piece about, and then whatever else he watched that week, he just does a "quick" (ha! ahahaha! ha!) little summary of his thoughts.

This week:

Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga (2024, d. George Miller - in theatre)

Point Blank (1967, d. John Boorman - Criterion Channel)

Purple Noon (or Plein Soleil, 1960, d. René Clément - Criterion Channel)

The American Friend (or Der amerikanische Freund, 1977, d. Wim Wenders - Criterion Channel)

Paprika (2006, d. Satoshi Kon - the shelf)

and, go!

---

Following

Mad Max: Fury Road, about as beautifully artistic and mentally and viscerally stimulating a post-apocalyptic action movie as we're ever to get, I was keen to say that Warner Bros. should just cut George Miller a blank check and make another one, whatever way he wants. I believe it was during the press junket for

Fury Road that Miller intoned he had written a full backstory script for Furiosa, the character played by Charlize Theron in the film. I was more than ready for that.

As time passed, the realization dawned on me that Furiosa's back story would have to be a pretty bleak one, given how in Fury Road she was headed to The Green Place from which she was abducted as a child. Was that something we really wanted to see? The abuses set upon a young girl in a very toxic and masculine society? We're aware of Immortan Joe and his harem of "wives" (barely more than breeding livestock as far as he's concerned) so it could get real, real dark. Did we want that?

What we really wanted was more Fury Road.

And you know what? That's almost exactly what Miller delivers with his new entry in the "Mad Max Saga".

In this nearly two-and-a-half hour extravaganza, told in five parts, we first meet Furiosa (Alyla Browne) in the fabled Green Place, a beautiful crevasse in the dead center of Australia (for the first time in the "Saga" were given an actual birds eye view, confirming, yes, this is Australia). A couple of marauders from the wastelands have found the place, and Furiosa, along with a younger sibling or friend raises the alarm. She attempts to sabotage the marauder while help comes but finds that, more than anything else in this lush refuge, she is the most valuable prize. Our first chase begins as Furiosa's fierce mother (Charlee Fraser) pursues the kidnappers through the desert, and yeah, it's relatively bare bones, but also completely intense. Furiosa is no hapless victim and finds her own ways of sabotaging the marauders.

Furiosa's story is one of tragedy, so things don't go so well against the vast forces of Dementus (Chris Hemsworth, Ghostbusters: Answer the Call). Furiosa is charged with protecting the location of the Green Place, while she is lobbed between Dementus and Immortan Joe. Realizing what fate has in store for her in Immortan Joe and his creepy family's care, Furiosa (now Anya Taylor Joy, The New Mutants) hides herself, disguised as a mute boy and a mechanic, she listens and learns. She observes the creation of Immortan Joe's first war rig, and sees the glory of its driver, Praetorian Jack (Tom Burke, The Lazarus Project [@Toasty...where's that review?]). Through a series of events, Jack becomes her new mentor. He's a hard, but kind man who wants nothing more than to help Furiosa be fully capable of surviving their horrid reality. As the two plot their long-term plan for escape from Immortan Joe, the two get swept into an increasingly urgent and brutal war between Immortan Joe and Dementus, which leads to more and more loss for Furiosa, but gaining an all-consuming thirst for vengeance.

If we look at the prior films in the overall Mad Max "saga" they are all structured differently. The original film is pretty much a series of vignettes, while the second film attempts a more conventional three-act structure (that I can recall). Beyond Thunderdome is more two distinct stories, and Fury Road is basically one long act. I like how Miller keeps you guessing with this series and the only thing you can really expect is to have an epic time with some crazy stunts.

While there was some themes to Thunderdome and Fury Road, Furiosa is pretty much a straightforward action movie. It maybe juxtaposes how different people deal with tragedy differently, but it's certainly not the driving force of the movie. Each of its five acts captures a day or so in Furiosa's life that shows her resolve and willpower in the face of intense combat and overwhelming odds against.

The acting is all exactly what it needs to be. Browne playing young Furiosa for the first hour of the film was unexpected but she was incredible. By the time we meet Joy's Furiosa she's been keeping herself hidden for years so her toughness is very quiet and reserved, until it shows itself in a very raw, emotional form. Praetorian Jack teaches her to control her rage and enhances her skill set, with Burke making Jack a very welcome reprieve from all the letcherous, vainglorious, egocentric and ugly men of the various worlds she's forced to inhabit.

Furiosa has about as much dialogue in this as Max did in Fury Road, which isn't much at all, so both Bowne and Joy's performance of the character is all in the physicality and the eyes. Conversely, Hemsworth is all words. While Dementus is a dangerous man, he's also a charismatic fool. He leads his people to ruin, but he has the distinct capability to always sucker in more people under him. Hemsworth's charm factor is so high, even when playing this despicable man. He has more dialogue than I think every other character combined, including a riveting monologue in the final act that is the flailing desperation of a thoroughly defeated egomaniac.

I liked how Miller and co-writer Nico Lathouris side-stepped a lot of the world building. Rather than shift its lens off Furiosa, it held tight with her throughout the film. It didn't spend more time with the society of the war boys, and didn't provide an origin story for "Witness Me" or even recycle any of the catchphrases from the prior film. Certainly they are a part of the story, but there is no character there to explore their culture through like Nux from the last film. Been there, done that. We really don't spend time with Dementus' crew as well because, as we learn, Dementus' crew is mercurial.

I found Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga to be a highly invigorating experience. I wanted to throw my arms up and cheers so many times, and I clapped with glee to see the war rig manufacturing process. It's a worthy prequel to Fury Road even if it is not quite its equal. I doubt anything can be.

---

One of my ongoing viewing projects is to watch all the various adaptations of Donald E. Westlake's Parker novels (written under the "Richard Stark" pseudonym). Though I've never read any of the novels, I became a rather immediate fan upon reading Darwyn Cooke's loving graphic novel adaptations. To date I've only managed to catch the awful Jason Statham-starring

Parker and the director's cut of 1999's

Payback, starring Mel Gibson. Of the eight adaptations of various Parker stories, arguably the most famous is the 1967 crime thriller,

Point Blank, starring Lee Marvin.

Based off the first Parker novel The Hunter, it finds Marvin's "Walker" (as Westlake notoriously refused anyone using the name without committing to multiple pictures) trying to come to grips with how he wound up in a prison cell with two bullet holes in his abdomen. The answer: betrayal. He got pulled into a job by Reese, a man in desperate need of money to pay off his debts, but the job wasn't a big enough score to pay Walker the split he was promised. Reese, having seduced Walker's wife, Lynn, sets him up for the fall. His only mistake was in making sure Walker was dead. Walker pulls through his injuries and sets out to not so much get revenge as collect what he is owed by any means necessary.

"The Hunter" is the same story Payback was based off of, and the rhythms of the story are almost exactly the same. Some of the characters shift in their personality and story, but inconsequentially. The real difference is in style. Payback is a very 1990's production, Cooke's comic adaptation is very firmly in the 1950's, while here it's so very 1960's Los Angeles, and it's glorious. I have to think everything Quentin Tarantino was trying to achieve visually in Once Upon A Time...In Hollywood stems from this film. I can't exactly put my finger on it, but the aesthetic of this film, from the streets of Hollywood, to every hotel room, office and mansion homestead are so exquisitely of the era, and it all just sings beautifully.

If I had to place the aesthetic it's that in the 1960's technology was just starting it's advancement into commercial sales, hi-fi stereos and phone intercoms, and doors that open and close with the press of a button. The ostentatiousness of the 1960's resulted in such heavy investment in electronics and mechanized devices that there wasn't the same sense of investment in making everything gold or highly ornate. Environments were very much wood framed with the brushed chrome of technology as an accent. Colours were pastel bases, muted, yet still vibrant. The buttoned down suits of the 1950s gave way to more mod suits in the 60's and the women adopted patterns and colours galore. There are times when I watch the film and wish I could tour around the setting more. This is a film where I wish I could just dive right in and live there.

I was about to say Lee Marvin as Walker was maybe a decade too old to play the character, but I just looked it up and he was 43! Five years younger than I am now. And he looks like he's cresting 60 in the film. Man that era of sunbathing, heavy drinking and smoking was hard on one's looks. That said, he's almost perfect for the vision of Walker, a big, broad man who can stop you dead in your tracks with just a look. There's a weird flashback where Lynn talks about when she met Walker, and it shows Marvin being playful and smiling with her, and oh, it threatens to undermine the entire image of the character. It's early enough on in the picture that Marvin has time to rebuild his image, but it takes a bit. The most immediate thing about Marvin's Walker that seems to deviate from Parker is his code of ethics. It seems at first like Walker is really trying to get revenge, it's not for a while where he really starts hammering it in that he's actually just after his money.

Angie Dickinson (Police Woman) is in the film as Lynn's sister, Chris, and she is everything to this film. She is a love interest for Walker, but definitely not the conventional "love interest" role. She is versed in working hard and doing what must be done, and as much as she wants to resent Walker for asking her to do so, she can't help but see a guy who very much does the same...only he's kind of an emotionless automaton. He frustrates her so much (as witnessed by the incredible scene where Dickinson goes full ham on Marvin until she's utterly exhausted and collapse to the floor) and yet it's clear she's got an incurable thing for him in spite of herself. She plays it so well. Her roles seems beefed up from other versions of this story, but maybe it's just that Dickinson does more with it. She has presence, and her character feels lived in, in a way maybe no other character does.

Boorman and his editor (Henry Berman) do weird collages throughout the film, mostly as flashbacks, which are not unwelcome but seem so ...primitive as a storytelling vehicle. Sometimes they work very well, acting as Walker's inner conscience or a dreamscape, but sometimes they feel like too much. There's a magnificent scene of Walker walking down a hallway, his ADRed footsteps "clop-clopping" away, setting the rhythm for Johnny Mandel's score to kick in, paired with some of that collage editing and it's just an masterful senses-grabbing scene that has been cribbed so much since, but probably never bettered.

---

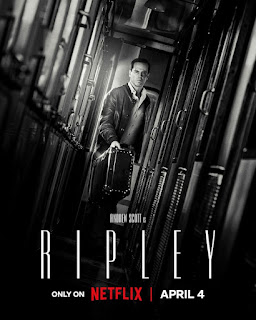

Another kick I've been on is watching any adaptation of Patricia Highsmith's Ripley series. I just did an obscenely long look at the 1999 version of

The Talented Mr. Ripley in comparison with the new Netflix series, and this drew me to re-subscribing to the Criterion Channel so that I could catch up on two earlier adaptations of Ripley stories.

1960's Purple Noon (not Purple Moon as I keep wanting to say) is a very French adaptation of The Talented Mr. Ripley, starring notoriously handsome actor Alain Delon (Le Samourai) in the title role of Thomas Ripley. I could go into a very detailed list of "differences" between this and the other adaptations of the novel, but I'll spare that in favour of just the broadest strokes.

The first big shift is how the film begins in media res, with Tom and Philippe Greenleaf (changed from Dickie) already best buds and hanging out in Rome. Philippe is already aware that Tom was sent by his father and Tom seemingly doesn't hide the fact from Philippe his criminal ways. The two are very boys' boys as they horse and pal around and fuck with other people for their fun. They pick up a woman and both make out with her (well it's more Philippe making out and Tom trying to get in on the action). Did I mention this film is so French. Marge likes Tom just fine but her relationship with Philippe seems strained by his cladding about with Tom. Tom covets everything about Philippe, his wardrobe, his carefree lifestyle, and his women.

Obviously this is the second big change. Tom's intoned homosexuality is completely absent from Delon's performance (and the script). When he kills Philippe, takes over his life, kills Freddie and returns to being Tom, he heads back to Marge and they start a relationship, and Tom seems genuinely happy. He has Dickie's life and he doesn't have to pretend to be him.

But as much as the story and performance are absent of any gay undertones, the lens in which we view the film is very queer indeed. The camera isn't in love with Delon, it is obsessed with him. Where in other productions the camera provides us largely Tom's point of view of events, lets us understand the story through his very warped eyes, here the camera is very disengaged from Tom's point of view and instead just ogles him. Though Tom is clearly covetous of Philippe's life, through the lens we see Tom as the ideal. He's much more attractive than anyone else on screen (and Maurice Ronet is not a bad looking guy, but pales compared to Delon) and we can never forget it.

Remember that old Late Night with Conan O'Brien bit "If they mated" where they would take two celebrities and show us what an adult offspring would look like if they shared their DNA? In Delon's case, he would be the "If They Mated" of Zach Efron and Jared Leto in their primes. Just the most piercing blue eyes and carefree floppy hair and fit-but-not-buff body. Just total ah-ooh-gah. I don't know what makes the lens gay male gaze as opposed to female gaze, but it's definitely feels like one and not the other.

The final big distinction of the various versions is the ending, in which Tom doesn't get away with it. And it's kind of clever and unexpected how they did it. Innocuous, sudden, and yet logical. I understand why in such an era they needed crime to be punished on films, but it does lessen the story, but so does the removal of the homosexual undertones. It's a very good production overall, but of course it is. As I stated before, the source material is one of the greatest, sure to be adapted over and over. Yet, it's the lesser of the three productions for not even daring to challenge the norms of the time.

---

I like the story behind

The American Friend (not

My American Friend, as I keep wanting to say) - the late 70's German-French production from noted auteur director Wim Wenders - almost as much as I like the film. As Wenders tells it, after his first few films were road stories largely improvised from loose scripts, he was looking for a fully scripted story for his next film. He became obsessed with Patricia Highsmith's novels and attempted to option every one of them, only to find they were all unavailable. This caught Highsmith's attention and she met with Wenders and clearly, as he says it, he "passed the test", and she offered him her new manuscript for her third Ripley novel before she had even sent it to the publishers. This was

Ripley's Game.

A coup for Wenders, in a way, but also a consolation prize of sorts. Wenders had approached actor-director John Cassavetes for playing the role of Tom Ripley, but he was busy. Cassavetes suggested Dennis Hopper (Super Mario Bros.) to Wenders, and Wenders came to like the idea. But when the time came to shoot the picture Hopper was still sidelined shooting Apocalypse Now. Hopper came off the set of that feature a practical zombie, drinked and drugged out of his mind, barely able to engage with the material and his co-stars. Bruno Ganz (The Boys From Brazil) was a popular stage actor who had only one screen credit, but Wenders convinced him to take the role. Ganz prepped endlessly and was very invested in the part. A few days into working with Hopper, who was very laissez-faire and freewheeled his lines, the men came to blows. Wenders let them fight it out, which led to an evening of drinking and a mutual understanding with Ganz softening his over-prepared stance and Hopper committing to starting each day prepping with the director.

It's a wonderful story in a way, I just wish it paid off on screen. Hopper's Ripley, wearing a stetson and cowboy boots most of the time, is certainly not the mind's eye view of Thomas Ripley, not akin to any other interpretation we've seen on screen. But aesthetics aren't everything. My chief complaint is that Hopper's performance just feels like he's in a completely different movie every time he's on screen.

Thankfully (I guess) in the first hour of the film, Ripley only has two or three short scenes which seem quite outside the main plot. Ganz plays Jonathan Zimmerman, a framemaker whose wife works at an auction house where Ripley peddles his illicit art wares. When the two are introduces Jon slights Ripley which causes him to spread a rumour that Zimmerman's rare blood disorder is terminal and that he's having money problems.

This catches the attention of some criminal types who are in a feud with other criminal types. They start to gaslight Jon into believing his disorder is terminal, and convincing him that he should be doing what he can to ensure the stability of his wife and son after his passing. All he needs to do is kill someone. It's very Highsmith in a Strangers on a Train but in a fun house mirror sort of way.

The job is done, and it's an intense set pieces that is wonderfully shot (no pun intended). There's a dangling thread of Jon having been caught fleeing the scene on camera but it's never picked up (and I'm not sure why). Ripley later encounters Jon at his frame shop, perhaps to taunt him, but Jon apologizes for his behaviour in their initial meeting and is very friendly. Ripley feels guilty. When he finds out the goons are trying to force Jon into another hit, Ripley tries to stop it before it starts, but ultimately can only intervene and help out. It's a very clumsy, blackly comedic, and similarly intense sequence on a high speed train.

Jon's secrecy with his wife and the weight of his deeds starts fracturing his marriage, but Jon thinks it's all too late. Ripley notes that the bad guys will try to clean up any loose ends, and they're going to have to go on the offensive. The film's final big piece once again plays out unexpectedly, with some irreverent turns that carry just as many nerves.

If not for Hopper, this is otherwise an really great film. It's not a terrific Ripley story, as the character is largely absent from the first half, but at the same time, given what we see of Ripley in the various adaptations of the first of Highsmith's novels, the character profile of an art dealer with criminal connections seems absolutely fitting. I just wish almost anyone else was playing him, but I think a 15-years-later Delon would have been perfect, as the film ventured between Hamburg and Paris.

---

Paprika is the final film made by Satoshi Kon, and what many regard to be his masterpiece. Having just seen all four in the past month, it's hard to not say they are all his masterpieces. He was such a thoughtful, incredibly curious and inventive storyteller, and as very much a latecomer to his career, it's still resonates as a huge tragedy that he died still quite evidently in his storytelling prime.

That all said, at least in first watch, Paprika is my least favourite of the quartet. It is so primarily because of my typical reaction to typical anime, which is a flinching revulsion. Where Kon's prior films seemed to defiantly break from typical anime styles and forms, Paprika seemed to be a sudden dive right into them, as if Kon just caught up on the prior ten years of anime that he had missed.

It's probably an unfair assessment.

And yet I kept wincing as I watched this. It started very simply with the character Paprika's haircut. Something about it screamed so loudly in my face, the way the curl of the hair covers over the cheekbones to both accentuate the jaw and highlight the eyes...almost more helmet than hair. It was the visual equivalent of chewing tinfoil or fingernails on a chalkboard to me. Just set me on edge.

A lot of anime (not a genre, I know, but...) has this thing where its action scenes or often entire stories operate in a stream-of-consciousness manner, because you can do anything in animation. But should you? The stream-of-consciousness side of this entertainment shouldn't bother me (I like Twin Peaks after all) but it's often just nonsense. Of course, I have limited exposure and so limited experience, but that is my experience and it does not appeal to me.

So when Kon's movie opens with a very intentional stream of consciousness-style dream sequence I was getting itchy, despite being obviously wowed by the director's continued masterful control over transitions, here rapidly transitioning between different dream realms. I basically bought into the film by the end of the incredible opening credit sequence, but my seatbelt wasn't securely fastened the entire journey.

Paprika doesn't really hold your hand. It may grab you by the shirt sleeve and give you a little tug from time to time, but it's not laying it all out for you, and it never establishes any sort of rules to what you are seeing. It's all very mercurial, dream logic.

Yet the story is nearly quite straightforward. In a near-future world, a company has invented a technology that can record people's dreams, but there's an exploit where people can actually enter those dreams using the technology. Paprika is Dr. Atsuko Chiba's alias when she enters the dreamscape, her very superheroic alter ego. Except someone else has stolen the technology, entered the dreamscape and is doing some real harm.

As Atsuko and the other heads of the project work with a police detective to try to suss out who is poisoning people's dreams, people start losing their minds in the real worlds and killing themselves. The news is bad, and the chairman wants to shut the project down, which would leave anyone using the dream recorder exposed to the psychopath.

This is a generalized summary and definitely not 100% accurate...as I said, it's a film that doesn't hold your hand. I found it difficult to embrace this world without understanding it first. The film talks about the newly developed "DC Mini" but doesn't really set us up for understanding the world as changed by the dream therapy technology that seems more widespread. Maybe they're both the same thing but it doesn't make sense that they are. I dunno, I probably need to watch it again.

The film toys with dreamscape logic, which means that often characters seem to wake up but are still in a dream, and then wake up from that dream to still be in a dream etc. It is a trick dream-based movies have been using for decades before and since. It's as effective as it is annoying.

There's this whole angle to Paprika that's about filmmaking and storytelling and camera perspective and collaboration and regret that seems very personal and personally appealing to Kon, but also is verrrry inside baseball for animators and cinematic storytellers. It's a side trip that ultimately has some leanings into one of the character's back stories but it also feels like an unnecessary tangent that stalls the mid-point of the film.

The character designs in this film in general feel more animated archetypes than in Kon's previous films (as Griffin Newman pointed out, it seems like three of the main doctors were visually designed after Professor X, Toad and the Blob from X-Men, something I picked up on as well, but was likely in mind after a binge of over 100 issues of X-Men comics and the 13 episodes of X-Men '97). I don't feel like I understood our main protagonist, Atsuko and her altar ego Paprika all that well. I don't really understand why Atsuko was doing call girl-style illicit meetings with patients where Paprika invaded their dreams. It somehow made more sense when the dream world was invading the real world and Paprika became an independent being from Atsuko, but I'm not sure why that made sense.

This wasn't a mind-twist, so much as a mind hurt. Again, maybe upon rewatch it will reveal itself more, and repulse less. I mean, there's an abundance of fat jokes and denigrating of an obese character in this so, cultural biases, along with my own anime biases, all got in the way.