Perhaps my favourite podcast over the past few years is Blank Check with Griffin and David, which finds actor Griffin Newman and critic David Sims covering the entire filmography of a director (one film per episode) specifically those who were given a blank check at some point in their career to make whatever passion project they want. It's an entertaining, inviting, insightful, thoughtful and incredibly well researched podcast which goes into deep (and sometimes juvenile) conversations about the director and actors and productions of the films they cover, frequently to the point where the podcast episodes are longer than the films.

They've just closed out covering the filmography of Jane Campion, a director I know primarily by name only, having only been exposed (no pun intended) to The Piano and Harvey Keitel's pecker in a high school art class (at least that's my recollection...I'll need some of the Hartviksen Heavies to chime in on that memory). It's only been with their recent Carpenter series and this Campion series that I've actually attempted to follow along, watching the films week-to-week before the podcast dropped. Fortunately the New Zealand auteur's earliest films were available on The Criterion Channel, unfortunately, 3 of her next 4 films, multiple-Academy Award-winning The Piano included, were not readily available for streaming. As such I will only be able to comment on 5 of her 8 films. They are:

Two Friends (1986) - Criterion

Sweetie (1989) - Criterion

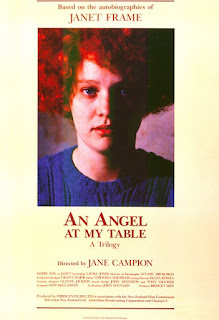

An Angel at my Table (1990) - Criterion

In The Cut (2003) - Netflix

The Power of the Dog (2021) - Netflix

---

Two Friends was a TV movie Campion made for Australian television that was screened at the Cannes Film Festival that year. It's the unassuming tale, told reversely in time, of two best friends who became distant. There's not any major stakes, just the simple falling apart of teenagers as they start taking different paths and pursuing different interests.

What Campion does to liven the proceedings up is both structural and visual. Telling the story in a reverse chronology, opening with the parents of one of the girls attending the funeral of one of her contemporaries, instantly disarms the viewer's expectations of what's happening (did the other friend die? Spoiler, no.) Campion also tells the story frankly from a female perspective, never delivering anything that could be considered expected or shocking. It's a grounded tale, to the fault of perhaps being too normal, too unassuming, not dramatic enough. Campion, with her limited budget, uses space to give her frames visual intrigue, something she does even more in her follow-up, Sweetie.

Being a mid-40s Canadian kid, I grew up on National Film Board-produced films playing on the CBC filling up those Can-Con hours. They were all of a sort, usually very slice-of-life because that's about all you could do on the meagre budget, with outdated equipment and production values, making for a cheap, unenticing production. It's clear there's an Australian equivalent to the NFB of Canada, they just happened to have a director with a sensibility that was capable of accomplishing a little more than the budget they gave her.

---

Campion's theatrical debut, then, is Sweetie, an off-beat family drama (though Campion calls it a comedy) about the impact the undiagnosed mental health disorder of the title character has on her family. Which isn't entirely true. We don't even see Sweetie, aka Dawn, for the first 25 minutes of the film. Instead we follow her sister, Kay, who is such a grating drag of a person.

"You're abnormal!" Dawn's boyfriend shouts at her late in the film.

She sure is

"It's your voice dear, it agitates him," her psychic says, referring to her intellectually disabled son.

Me too.

I understand Dawn. She has a mental illness in a time where such things were still not generally understood and help was not easy to obtain. I understand the stress on mom and dad, and what's happened in their fractured relationship (well, somewhat...not sure I get the dude ranch mom was hanging out at, a very curious aside).

But Kay, I don't understand her at all. She's abnormal, and her voice agitates me. There's a Kids In The Hall recurring sketch with two characters with drab voices, deep frowns, bad posture and hangdog eyes with the catchphrase "Nobody likes us." Kay could be their third.

Everyone in this movie is so damn ineffectual, they have such an utter inability to deal with the world around them or affect any meaningful change in their lives. The characters will tell each other what to do and they'll do it, so long as nobody tells them to do anything differently. It's no wonder Dawn is the way she is, nobody seems to have done a damn thing about it, they just threw their hands up in the air and said "this is how it is."

There are some good, subversive comedic beats in this film, but they do get lost in these loping cartoon characters. The dialogue is so very stilted, and that stiltedness is often spotlighted by the edits Campion makes jumping between her oddly-framed portraits. I found the pacing of the film and timing of the actors to be nearly intolerable. But the weird artfulness that Campion brings is hard to ignore. The spare use of space as she will frame a figure in maybe one eighth of the frame is one of the more captivating elements.

---

Campion's next film is a time-hopping, globe-spanning epic, at least in comparison to her earlier features, as she adapts New Zealand author Janet Frame's three early autobiographies into one film.

An Angel At My Table is a frequently tedious, often uncomfortable, occasionally upsetting, sometimes uplifting adaptation of Frame's work (each given a chapter designation in the film). Campion's visual acuity is without question, but as a biopic it misses the mark by wanting to cover it all, leading to a film that feels like a barrage of vignettes rather than a cohesive story. I'm not sure it earns its near-160 minute runtime. I came to learn later this was designed for TV, to be presented in 15-minute increments, which really makes more sense to me. Visually it feels cinematic, but structurally it felt more TV.

It seems that Campion, in putting her attention towards trying to relay as many aspects of Frame's life (from childhood to her 30's) lost the ability to draw focus to themes or commentary. Things are presented in an "as they are" way, with little insight or reflection as to why they might be (maybe this mirrors Frame's writing? I can't say). There is definitely a throughline to me made of the detrimental influence of the patriarchy on Frame's life, and how beholden or deferential to it she increasingly becomes to it, but it's never reflected upon. It almost seems incidental, where it really should have been pulled into focus. Perhaps it's because, at least where we leave her, she hasn't escaped it, or even really identified it.

It's hard to convey adequately, even in a two and a half hour movie, the overwhelming impact of an abusive father, the death of a sibling, misdiagnosed schizophrenia leading to 8 years of incarceration and shock treatments, more death, being shuttled from New Zealand to England alone, being domineered by a neighbouring man with ill designs for her, a first time love affair with (presumably) an older man, and yet more death. The only time I really felt the weight of all this upon Frame was when she actually experience joy or happiness or elation in spite of it, otherwise the heaviness is present but it's like she's not aware of it.

By the end, despite spending so long with Frame, I still don't feel like I know her, or really, fully understand her motivations, or feel like the film version of Frame understands herself in any way. It's got plenty of memorable moments but ultimately it's unsatisfying.

---

After the massive success of The Piano and the underperformance of her follow up with another period drama, Portrait of a Lady, Campion tried her hand, for the first time, at a modern story. Not only that, but a psycho-sexual thriller, a notoriously difficult to pull-off genre. In The Cut bombed hard, both critically and commercially.

In 2003, nobody wanted to see Meg Ryan, America's other, lesser, sweetheart, playing a horny, sweaty, terse professor who gets wrapped up in a string of gruesome serial murders. Ryan was the rom-com lady, the heart Tom Hanks had to win over. She wasn't the get drunk, handcuff a detective to a radiator and fuck him senseless on screen vixen. She got pigeonholed.

As flawed as In The Cut is, Ryan's performance is pretty great. She's an extremely nuanced character, with tics and curiosities and anxieties. This was a role originally intended for Nicole Kidman, and it seems exactly like a Nicole Kidman thing to do, but it's only more interesting because it's Ryan, and because she does pull it off so well. I've never been a Ryan fan, I just have no attraction to her romcom persona, but I thought she was so engaging here. She's so in control despite being out of control, it's a high-wire act which she negotiates perfectly up until the sloppy final act (which, I learned, is actually very much telegraphed from the beginning, and apparent upon rewatches...but it still feels rushed and messy).

There's a lot going on in this movie. I mean, Kevin Bacon's in it... unbilled! Mark Ruffalo is the red herring love interest, and the film teases constantly the idea that his detective investigating the murder may well also be the murderer. Unfortunately this whole tension rests on the fact that Ryan withholds a key piece of information until the climax of the film. In between, they have a lot of sex and talk a lot about sex and look at gruesome murders and connect somewhat and stuff. The sex and nudity is more menacing than hot, but it has such a different energy than the usual male-directed or American erotic thriller, there's a comfort and confidence you don't usually see. Rather than feeling like "aww, Meg Ryan", it was more "good for you Meg Ryan".

Unlike Campion's earlier films with a lot of perfectly framed and positioned shots, here she has a roving lens, getting distracted but also taking in information. My favourite shot of the movie finds Frannie riding in the back seat the detectives' car, having her focus suddenly drawn to a woman darting down the sidewalk and around the corner. There's a similar moment, just a strong visual curiosity, when Frannie is on the subway, and at a stop stands a bride, groom and some of the wedding party on the platform, the bride's makeup all smeared as if she were crying. There's dozens more just ancillary shots like this, so many that they intentionally obfuscate meaningful information happening in the background. Kind of ingenious.

In the Cut is a recent reclamation project for a few critics, and it makes sense. While its many disparate nuances may not all hang together it's still a really engrossing watch and a great entry in the genre.

---

Going into this film, armed with but one semi-spoilery tidbit of "all is not as it seems", I could telegraph much of where it was going from the onset...which could be a criticism if this were supposed to be a film of twists, but it's not. It's two "surprises" are laid pretty bare if, like Peter, you know how to use your eyes in ways other people can't.

The opening hour is largely establishment, and I admit to being a little distracted during this part, as we do nowdays with phones in hand. But the second hour, once Smit-McFee's Peter reenters the picture, and that crackling "what's really happening here" dynamic sets in with Cumberbatch's filth-lord Phil, it just sizzles with curious tension. I was rapt.

This is a commentary on identity, as it relates to masculinity, as well as queerness, and how these change and evolve from one generation to the next, yet how often the older generation gets stuck in their perceptions of how things have to be.

I like how Plemon's George knows Phil's whole schtick is just an act, unlike the others he's neither afraid of nor charmed by his brother, but he's also incapable of affecting his behaviour. He seems to know there's a mask his brother puts on but he's not entirely sure how to explain why (or perhaps he doesn't want to admit it), if he did perhaps he could have saved Rose a lot of grief).

Dunst's Rose, unfortunately, gets short shrift here as a character. Fragile and anxious, she succumbs to Phil's psychological intimidation, and has nothing but nerves when it comes to her sudden shift in status. She spends most of her time with her nose in a bottle which only seems to diminish her even further in Phil's eyes. I maybe missed a few tidbits about Phil's relationship with women in the past, unless it was just that bit about his mother getting him a prostitute at a young age, ensuring without a doubt he would be a man, but Phil clearly hates women, and has little use for them.

Campion's lens is back to being so focused here, studying intensely. The vistas and colours are gorgeous. Greenwood's score pulsates, enhancing the uncertainty of what you're seeing, hinting at something moving under the surface, muscles knotting under the skin.

This one's going to simmer in my mind for a while I can tell. As often as I picked up on what Campion was foreshadowing, I still felt the energy of not fully knowing what was happening between these characters. I'm curious if, on rewatch, if knowing exactly where it's going changes how it plays.

Rockin' Ronnie (RIP) did indeed fawn over The Piano in art class. I remember he was enthralled with an overhead shot of a cup of coffee being poured or stirred -- he paused on that scene for a couple minutes in rapt. I recall you & I digging the tiniest of throwaway scenes involving Anna Paquin's character telling a story and there's a cut to an animated person on fire that we added sound FX to.

ReplyDeleteOk, yes, the memory is not utterly fallable. Good to know.

DeleteI had a distinct memory of Ronnwell (RIP) warning us that there would be a penis in the film and that we were all mature enough to handle it. Come to learn that Campion likes to have a penis in all her films. Usually a totally casual peen, not a gratuitous one.

The weird animated aside of the Piano (which I had completely forgotten but now recall) has a sister sequence in In The Cut which jumps from the gritty, sweaty, handheld pov streets of NYC to a black and white, silent film styled, sequence of adults skating in a very studio set-like manufactured outdoor rink. This aside is visited a couple thimes, including a trippy sequence where the male figure skates over the female figure disarticulating her multiple times.